Author: chris

-

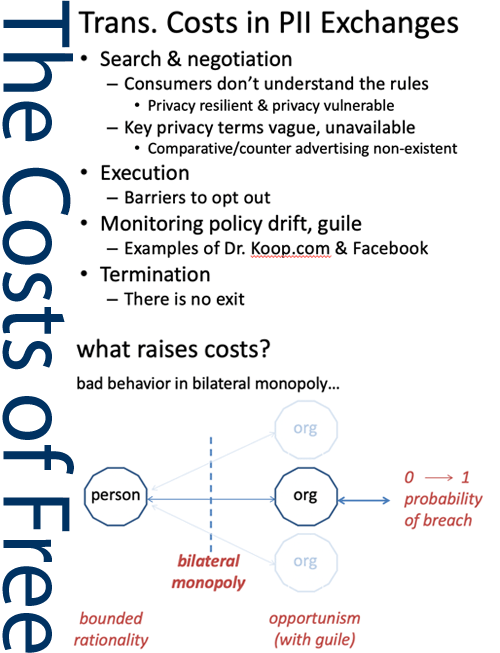

“Zero Price” != Free: How “Free” Can be Anti-Competitive

In articles with University of Washington Professor Jan Whittington (Ph.D., UC Berkeley 2008), we explore consumer-oriented internet services through the lens of transaction cost economics. This work shows how personal information transactions—“free” exchanges—can be uneconomical: consumers cannot exit these arrangements; they create lock-in; and ultimately this is a deep moat against competition. Free transactions enable companies to…

-

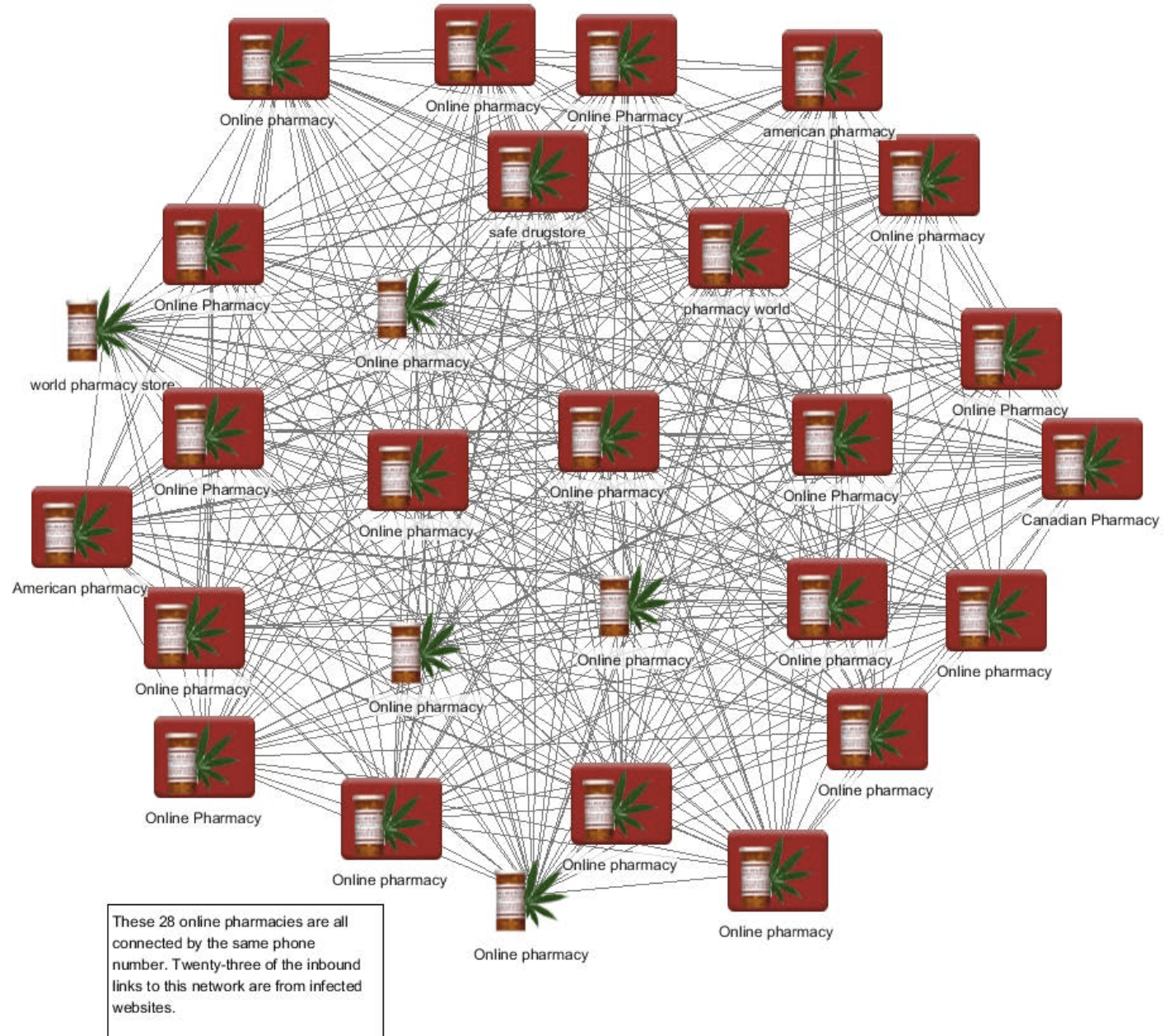

Internet Tracking & Cybercrime

We have performed terabyte-scale studies of internet tracking and of cybercrime networks, using a series of tools including Palantir Gotham, Palantir Contour, mitmproxy, STATA (Here is my STATA Cheat Sheet), Python, and a custom-built crawler. This has led to several insights, including new forms of consumer tracking in the wild (flash cookies, cache cookies), the demonstration…

-

Federal Trade Commission Privacy Law & Policy

This book is a historical account, an institutional study, and a discussion of policy choices made by the U.S. FTC. The FTC’s creation in 1914 represented a turning point in American history where skepticism of expertise and central regulatory authority was overcome by the need to address contemporary market conditions. My book connects today’s tussles over privacy…

-

Inactive Courses

Privacy Law for Technologists Information privacy law profoundly shapes how internet-enabled services may work. Privacy Law for Technologists will translate the regulatory demands flowing from the growing field of privacy, information security, and consumer law to those who are creating interesting and transformative internet-enabled services. The course will meet twice a week, with the first…

-

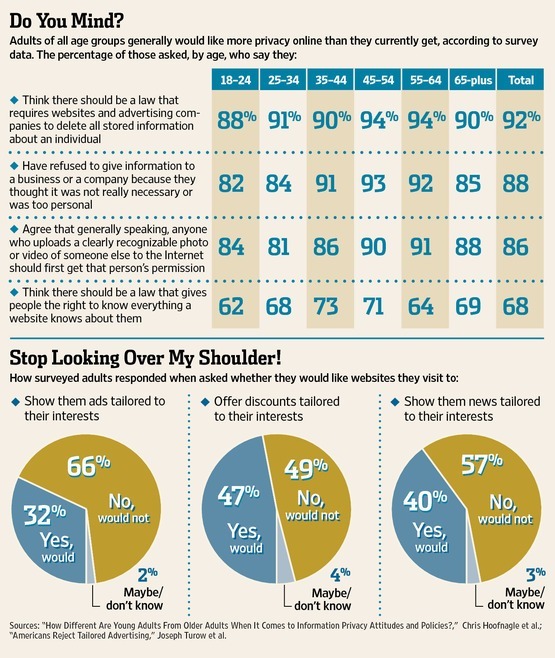

Consumer Knowledge & Attitudes

Alan Westin’s well-known and often-used privacy segmentation fails to describe privacy markets or consumer choices accurately. It describes the average consumer as a “privacy pragmatist” who influences market offerings by weighing the costs and benefits of services and making choices consistent with his or her privacy preferences. Yet, Westin’s segmentation methods cannot establish that users…

-

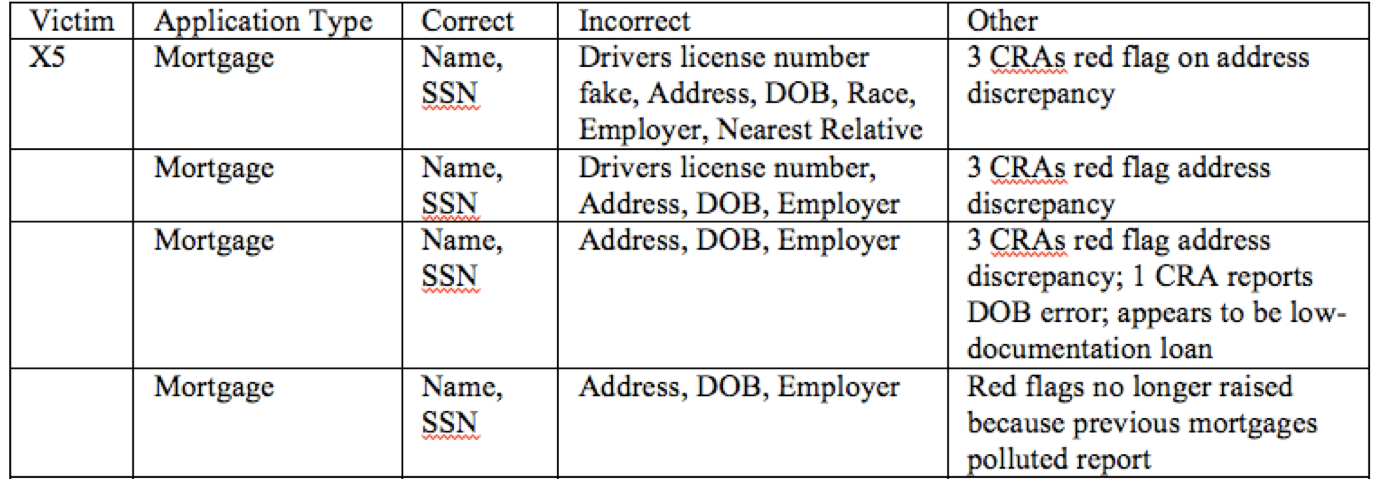

Root Causes of Identity Theft

In a trio of articles (for NSF-TRUST), I showed how identity theft is an externality of credit granting, where costs of fraud are spread among victims, merchants, and society generally. For instance, the image below is summary data on an identity theft victim who I interviewed–the impostor in the case made…

-

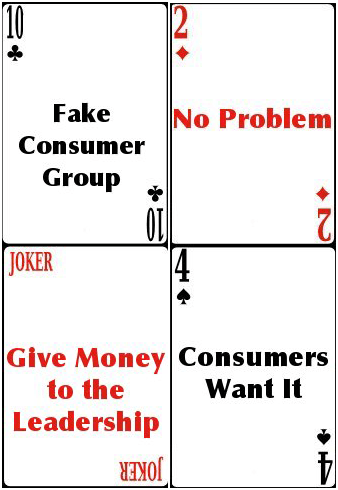

Denialism

Before coming to Berkeley, I worked in Washington, DC as a privacy advocate. I was struck by the character of policy debates there. Industries lobbied using a blend of libertarian and one-eyed public choice argument, repeating it so often that to me it sounded like simple cliché. In fact, it wasn’t debate, it was intransigence.…

-

Assessing the Federal Trade Commission’s Privacy Assessments

Why read this article? This short article points out the big differences between an “audit,” and an “assessment,” the latter of which is the tool used by the Federal Trade Commission to oversee companies that are subject to consent decrees. “Assessment” is a term of art in accounting wherein a client defines the basis for…

-

Comments on the CCPA

I filed the following comments today on the CCPA to the CA AG. March 8, 2019 VIA Email California Department of Justice ATTN: Privacy Regulations Coordinator 300 S. Spring St. Los Angeles, CA 90013 Re: Comments on Assembly Bill 375, the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 Dear Attorney General Becerra, I helped conceive of…

-

Amsterdam Privacy Conference 2018

Opening keynote talk on The Tethered Economy, 87(4) Geo. Wash. L. Rev. ___ (2019)(with Aaron Perzanowski and Aniket Kesari), Amsterdam Privacy Conference, Oct. 2018.

-

Syllabi

I’m getting a lot of requests for my syllabi. Here are links to my most recent courses. Please note that we changed our LMS in 2014 and so some of my older course syllabi are missing. I’m going to round those up. Cybersecurity in Context (Fall 2019, Fall 2018) Cybersecurity Reading Group (Spring 2020, Spring…

-

Embrace legitimate cost–benefit analysis, recognize that much of it is not legitimate

From Federal Trade Commission Privacy Law and Policy, Chapter 12: The FTC is surrounded by critics who urge that Agency actions must be more “rigorous” or based in the “sound economic policy” of cost–benefit analysis. There is some merit to this argument. As Peter Schuck explains, cost–benefit analysis has much to offer policy-makers.39 Consumer advocates…