Revisiting Arthur Leff’s Swindling and Selling

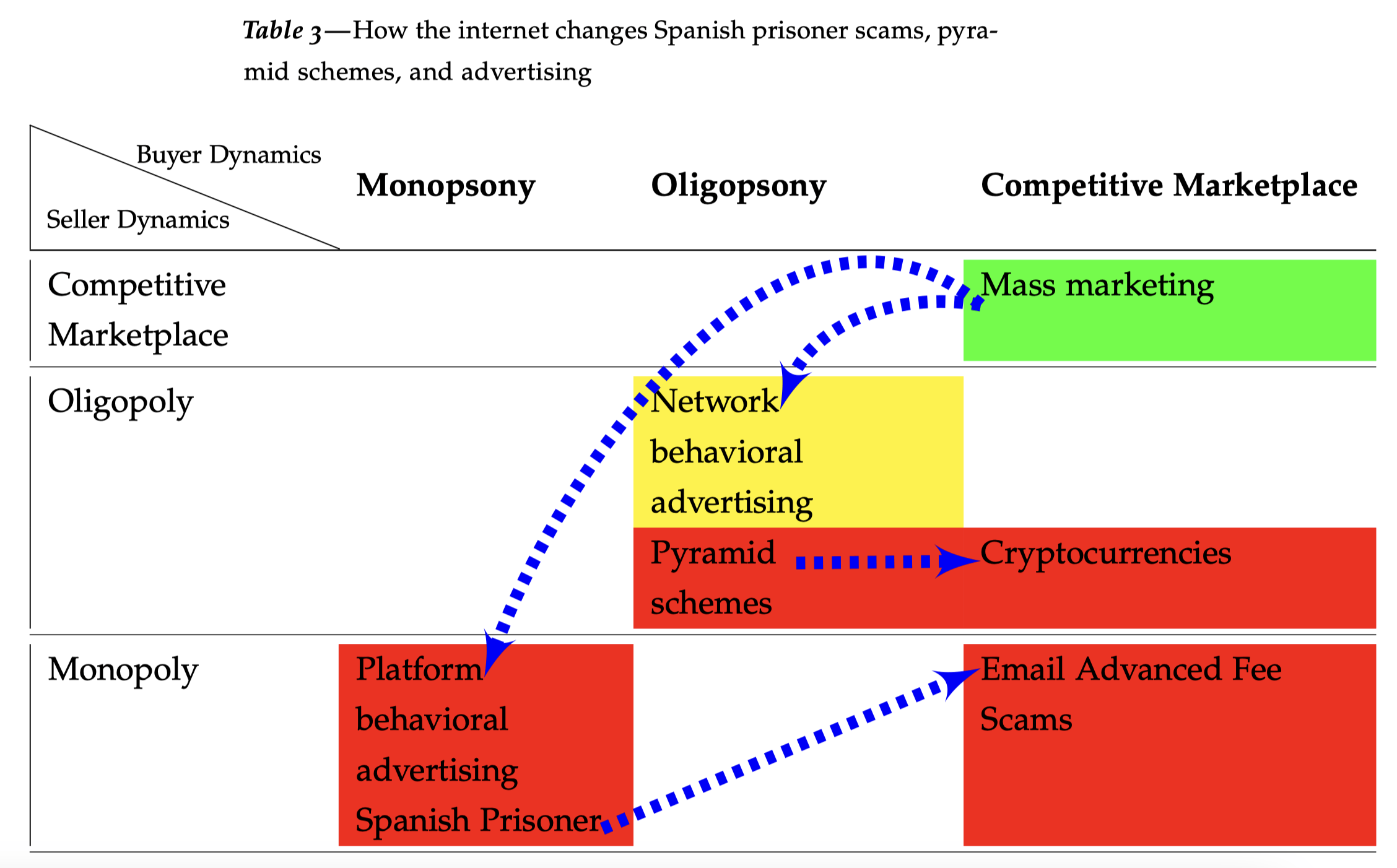

Yale Law Professor Arthur Leff wrote a powerful, market-structure analysis of consumer fraud in his 1976 Swindling and Selling. That work is more or less lost to history. Leff explained that con artists attempted to impose a false economy on marks. In a perfect congame, such as the Spanish Prisoner, this false economy was a bilateral monopoly. But in other, less perfect congames, the con artist moved the mark into some otherwise undesirable market relationship, such as an oligopoly.

Regular selling is sometimes difficult to distinguish from swindling, because selling often incorporates minor deceptions. But the difference is that those deceptions occur in ordinary, competitive consumer marketplaces, where consumers have more choice among sellers, and in turn sellers are making offers to all consumers rather than to a targeted individual.

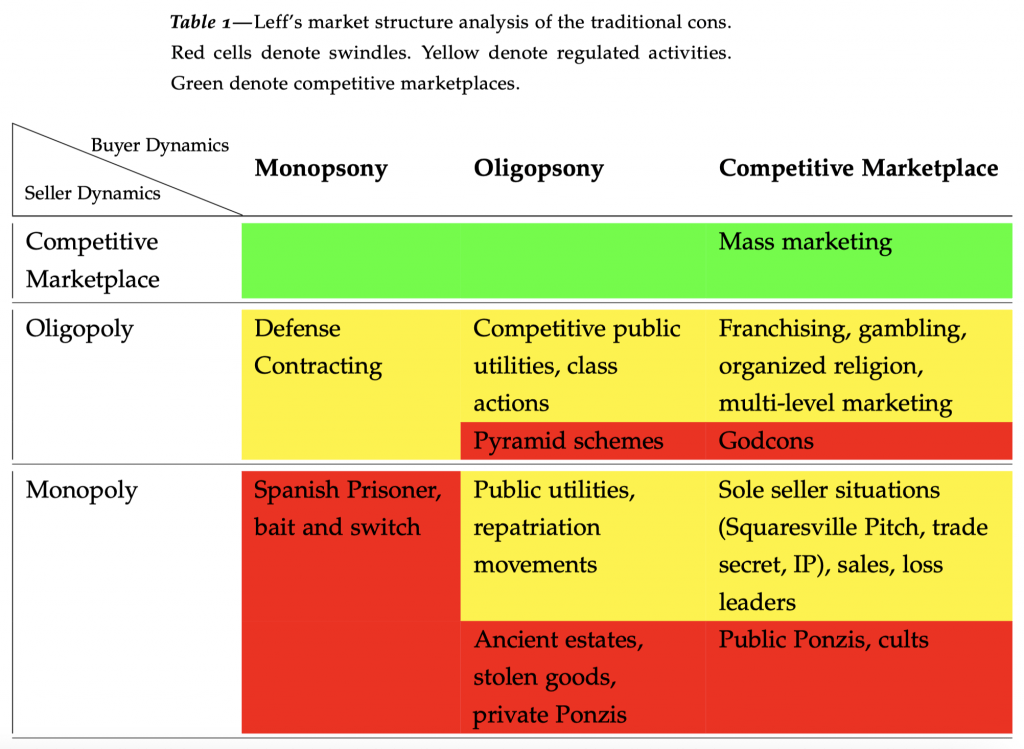

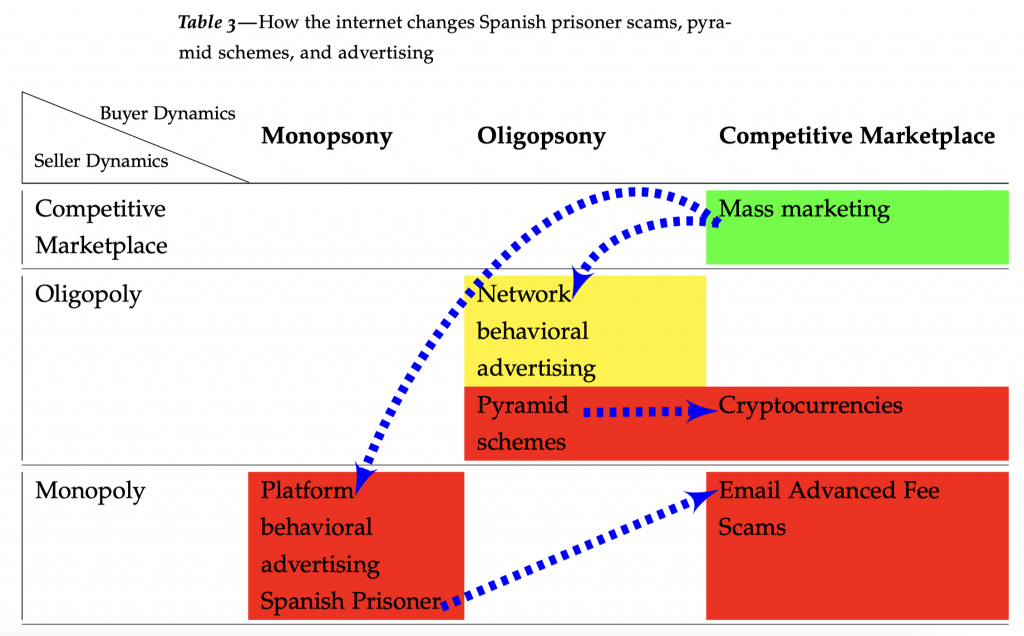

This article contributes to Leff’s work by placing modern, internet-based congames in his market structure framework. It argues that most congames have been refactored into advanced fee email schemes, and that these are much more powerful because con artists can easily target people worldwide, because they can lead marks into a long con without ever encountering the mark in person.

Ponzi schemes still exist on the internet, despite the availability of information that might help marks see them as such. Bubble logic and the claques of early investors who win in Ponzi schemes still make these cons profitable. As an example, cryptocurrencies share the character traits of earlier Ponzi schemes, right down to Leff’s claim that they must offer a “grey box” business model to swindle people. The blockchain is a perfect grey box—technically transparent but actually inscrutable to the retail investor.

Finally, online behavioral advertising has been critiqued for many reasons. This article adds a new way of thinking about OBA: if we want to realize the promises of OBA, we have to place consumers into a monitoring environment characterized by monopoly, a complete one where nothing is secret to the advertising platform. That is, OBA requires a bilateral monopoly market structure.

Recognizing that OBA has the same fundamental dynamics as the Spanish Prisoner or the bait and switch might cause use to decide to reject OBA, or to subject OBA to rules similar to those imposed on other monopoly actors.