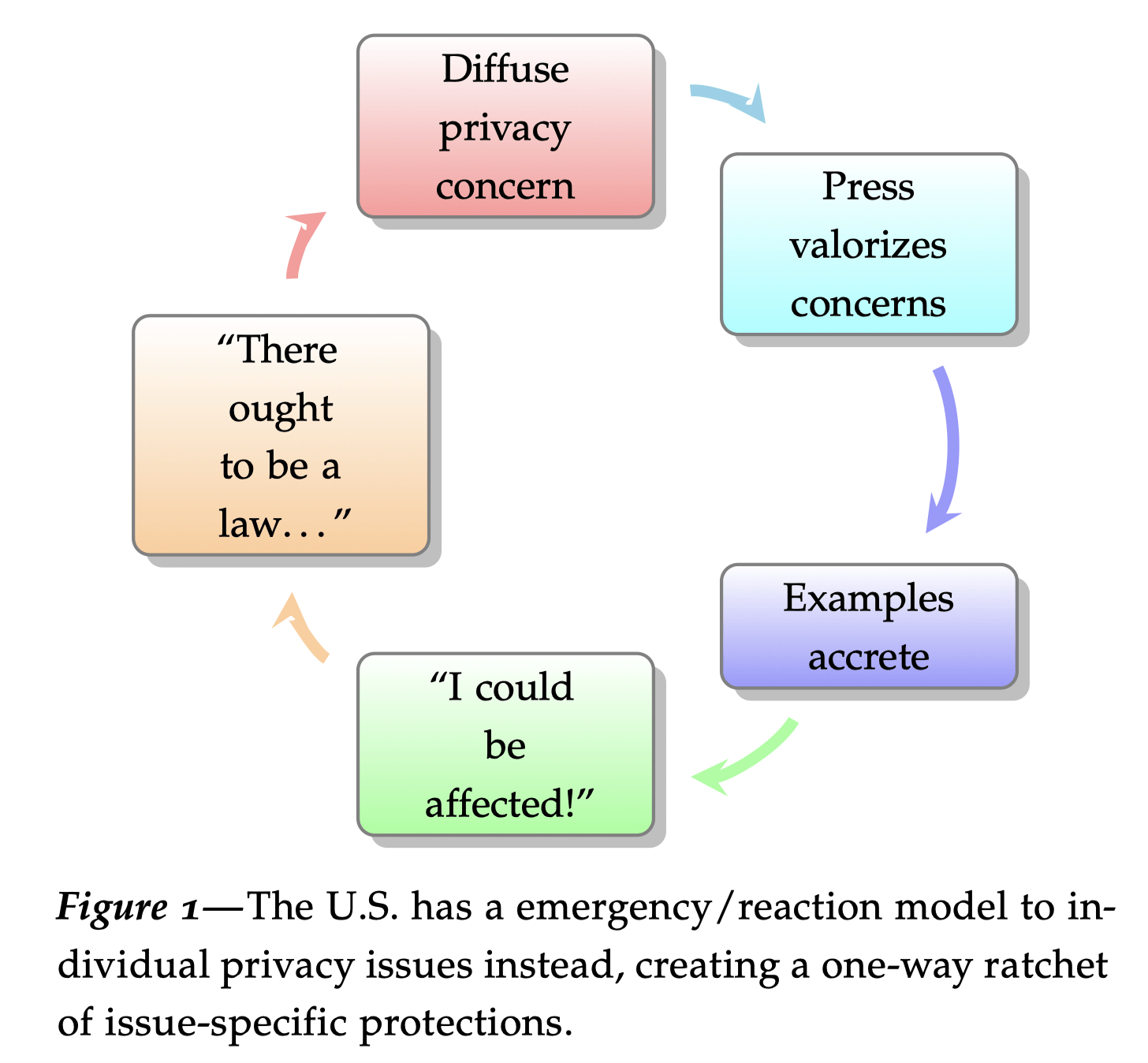

In this essay for a lecture at Stanford University, I attempt to explain consumer privacy as a deterrence theory strategy. I argue that privacy does have methods of analysis, based in fair information practices, while popular use of the term “privacy” is loose, a shibboleth representing uncertain values.

This wide-ranging essay then goes on to explain how privacy is a rational strategy based in deterrence theory concepts. This is because giving companies data and attention transfers power to companies. The consumer becomes vulnerable to a class of adversaries with mixed, changing, and even unknowable motives. Data and attention enables companies to shape our interests, tastes, and activities. In some cases, this shaping is cooperative but in others, companies are in competition with consumers’ interests (most obviously when that shaping stokes insecurities, addiction, or encourages other irrational behavior). I tie this interest in shaping to the creation of audiences, and show how platforms’ incentives are to create user groups comprised of miserable people—the kind of people who scroll and click all day.

Platforms have high power incentives to recognize [people vulnerable to extremism] and then to turn them into engaged platform users. Understood this way, our struggles with disinformation, both left- and right- wing, can be seen as a symptom of business competition for attention.

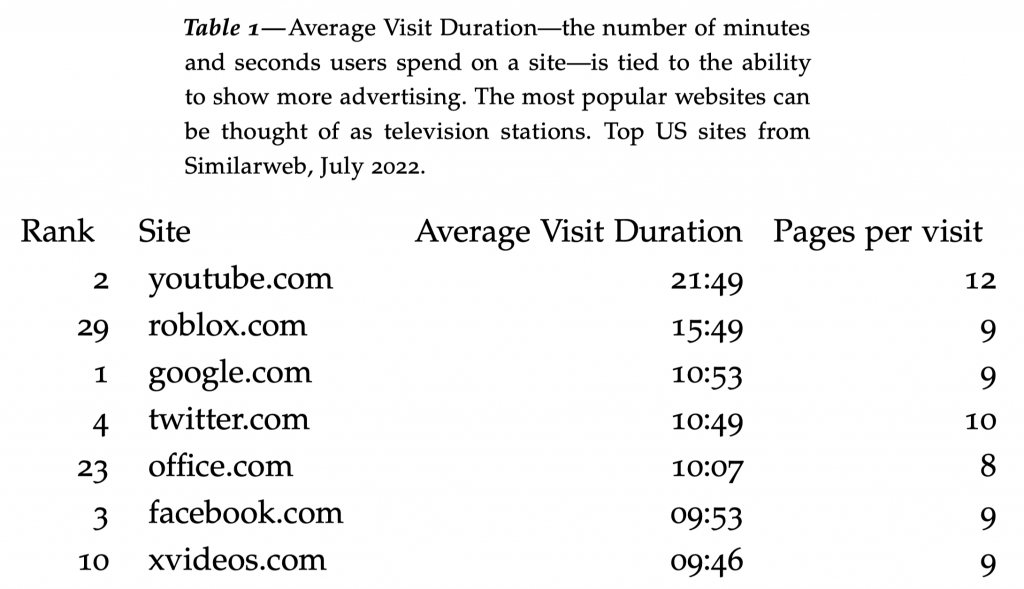

The Web really is just television.

Prediction is the other risk that drives privacy concern. We might want others to predict our greatest needs and wants. But upon inspection, that’s only the case when others care for you. As Zuboff points out, platforms don’t care for one’s welfare. They are indifferent to our situation, so long as it involves eyeballs on their site. This is why YouTube is a cesspool—YouTube lacks incentives to clean up its platform because there is an audience for any kind of terrible content. Platforms can monetize disinformation about vaccines or videos that challenge your children to see how long they choke themselves or terrorist recruitment material. They make money based on how much you watch rather than what you watch.

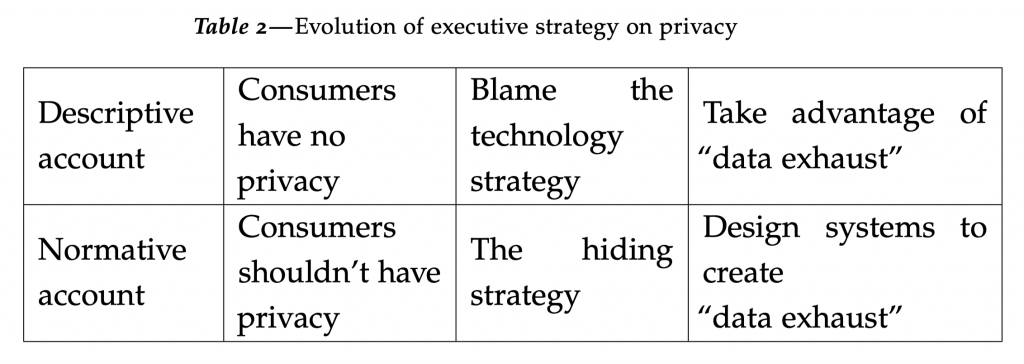

Another theme surrounds the normative values of technology executives. I recount how Scott McNealy’s “you have no privacy” statement was descriptive—he was recounting what he believed to be the state of play given the rise of a Database Nation. But by the time Google becomes dominant, the statement became platforms’ normative commitment about privacy. My proof of this comes from the wealth of research that shows that technology executives know that consumers want less tracking, and so they lie or dissemble to distract the consumer from technological realities—even degrading the security of systems in order to keep up user surveillance. What Zuboff calls the “hiding strategy” comes from executives who think consumers do not deserve privacy, so it is okay to lie to consumers.

Technology executives see nothing wrong with the the logic of complete surveillance and the need to hide it from consumers. Why? Because technology executives do not see privacy as a legitimate interest. Remember Scott McNealy’s point was descriptive and now it is normative. Companies do not think you deserve privacy.

How executive strategy on privacy has changed to a “collect it all” mentality—and why it is okay to lie to consumers about it.